This is a series delving into the passion and flair that makes the Copa América a worthy tournament of the sport we love. We hope through the succession of these articles you find joy in the tillage of the tournament and discover what makes soccer, fútbol.

Please consider reading the series in order, it’ll make the journey flow better. But don’t worry, each individual piece will make sense on its own too. It’s your choice. This is No. 2.

If you haven’t read the first article of the series, Copa América Centenary: Preview For The 45th Installment, you can do so here.

Last time I mentioned:

And so is it any surprise that the Copa América embodies such a stark medium for the clash of gritty, “dejalo en la cancha”, bravado mindset with that of the technically artistic, “la pausa” and downright “colmillo”?

Let’s dive into Latin American terms and philosophies and uncover the Copa America Legends that embody these ideals.

La pausa literally translates to ‘the pause’. La pausa is the most difficult move to do in soccer. It involves placing your foot on top of the ball and ‘pausing’ the game. Sounds easy right?

Well, the beauty in la pausa is having the forethought, the vision, and the inner peace during a battle of soccer to dictate the speed and the momentum of the game.

It’s a move most often done by your most technically gifted player, maybe a CAM, but la pausa is more spiritual than technical. The technical aspect isn’t a coincidence, but you cannot perform la pausa correctly unless you can read the flow or the spirit of the match.

During the chaos of a match, it takes something special; it takes clarity, it takes la pausa, to freeze the game, to slow the momentum of the opposition and re-start your side.

Anyone can step on the ball, but only few can do so at the right moments. When your team is lacking possession, your defense is under a constant siege of attacks, team lines are starting to falter, tactically players are floundering, the spaces behind your back line are unzipping, and the opposition seems to be on the brink of scoring.

That is la pausa.

What better Copa America Legend to introduce than Carlos Valderrama, and his fantastic hairdo, the master of la pausa?

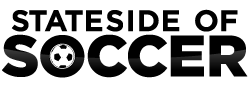

Mandatory Credit: David Cannon/ALLSPORT

El Pibe, or “The Kid” is a Colombian national football team legend. It’s probably a combination of his golden locks, being the most capped played for Colombia and his classic deep-lying play-maker style of fútbol.

Valderrama doesn’t run. Well, at least not as much as you’re used to seeing now a days.

As a child, I remember asking my dad, while watching the Copa, why doesn’t Valderrama run.

My dad calmly responded, “Why would he need to?”

Why indeed?

Valderrama had a presence on the pitch. He had taken his technical ability, tactics, vision and la pausa to the extreme. He had mastered it. Why run after the ball when you know you’re going to be the first person to receive the ball as soon as Colombia regains possession?

His game was never flustered; he played with the most inner piece and calmness that I have ever seen displayed by a fútbol player.

He achieved all of this via la pausa.

But there’s more than one style of play in Latin America.

Colmillo directly translates into the word ‘tusk’. But that’s kind of a loose translation, more appropriately it would be translated into ‘canine’, those long teeth that are symbolic of vampires.

It’s also slang. The word comes from Mexico and represents someone who is cunning, experienced and maybe a little mischievous.

Colmillo is fouling the opposition during a counter attack to get players behind the ball, taking the ball to the corner flag in the dying minutes of the game, fixing your shoes as you’re substituted out to waste time, and so on.

It’s anarchy.

The move with the most colmillo in the history of fútbol has to be Diego Maradona’s ‘hand of God’ where he stuck his arm out above his head to score a ‘header’ in the 1986 World Cup quarterfinals.

But this is the Copa America, not the World Cup and Jorge Campos must take the cake here.

The legendary Mexican international goalkeeper kept it fresh. His goalkeeping outfits themselves personified colmillo. His jersey and shorts often matched with zigzagging lines of bright fluorescent greens, yellows, oranges and pink.

Analyst called his soccer style eccentric. None of it was eccentric; it was all colmillo.

Campos thrived by playing outside the 18’ yard box. Yes. You read that correctly. He would often play with the ball outside the box, taking on the opposition, and sometimes when playing for his club Pumas, he would take the field as a striker.

During a corner kick, he’d be waiting on the offensive third of the field, collect the rebound, take a player or two and then cross the ball.

Think Manuel Neuer times ten.

He scored bicycle kicks off corners, took penalty kicks and whatever else you could probably think of.

Oh, did I mention that he’s also a world-class goalkeeper? Don’t let his small frame trick you. He’s an excellent shot stopper, commander of his box, leader and he’s downright passionate.

If that isn’t colmillo then, I don’t know what is.

If colmillo isn’t you style then may dejalo en la cancha may be. This is the simplest, most unapologetic mindset for a Latin American game.

Dejalo en la cancha means ‘leave it on the field’.

It means whatever is going on in your personal life has no room for the pitch. Throw it all aside and instead cast all of your effort, love, hate, frustration, desire, and pride towards winning a match of soccer.

That’s it. There can be nothing more asked of you if you step onto the pitch with a dejalo en la cancha philosophy.

I’m prideful to think that we Americans, have an American soccer legend as the master of dejalo en la cancha.

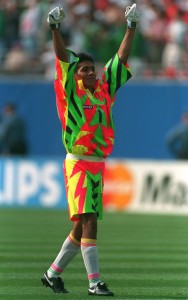

Alexi Lalas may divide opinions, but dejalo en la cancha is all about separating the world from what you need to do in the next 90 minutes. Lalas has never had a problem with that, so why should we?

With 96 international appearances, this man gave everything he had to the USMNT. His best displays were for the 1994 FIFA World Cup at the heart of the defense. You could not out work, or sacrifice more on the field than Lalas did. His fire red hair reminds me of what Sergio Ramos would look like if he were the son of Greek/American parents growing up in Michigan.

Once he had a conflict of schedule between his club team and the USMNT. His club Padova was in a playoff game for possible relegation if they lost. USMNT was in the midst of a cup-tie against Nigeria.

So he did what any sane man would do. He played his match for Padova, and as soon as the match ended, he flew to the USMNT and played the second half of the cup-tie.

Even now at the age of 45, Alexi Lalas would heed the call from the USMNT. The ball may get past him, but the attacker won’t make it that far.

Well, now that you know the philosophy and legends, let’s dive deeper…